As Seen In

How Japan ‘Changed the System’

Japan’s Bold Steps

By: Iain Marlow

ASUKE, JAPAN The Globe and Mail Last

updated: Saturday, Nov. 14, 2015 3:41PM EST

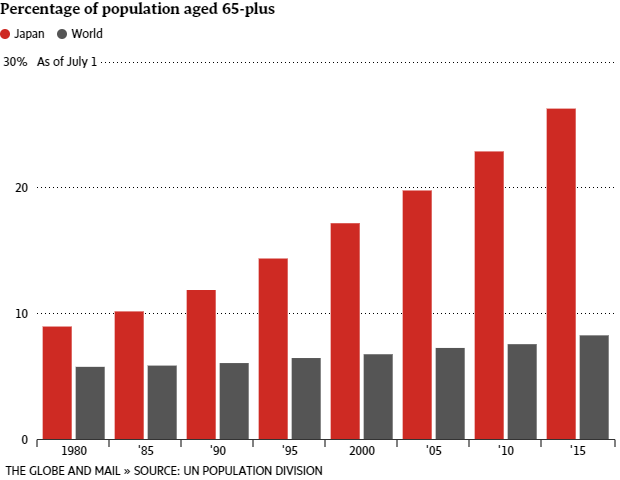

People over the age of 65 make up a quarter of Japan’s population, and it’s on track to reach 40 per cent. The top-heavy demographic creates huge challenges

for government and the economy. Now the country is tackling the problem with innovative programs, including everything from comprehensive long-term-care

insurance to robotics.

Yuriko Nakao/Bloomberg

Yuriko Nakao/Bloomberg

This is part of the Globe and Mail’s week-long series on baby boomers and how their spending, investing, health and lifestyle decisions could affect Canada’s

economy in the next 15 years. Is Canada ready for the boom?

For more, visit tgam.ca/boomershift and on Twitter at #GlobeBoomers

The country road leading into the small Japanese community of Asuke meanders past bamboo groves, rice paddies and traditional tiled-roof houses, some of which have trees in the yard brimming with oranges in the late October sun. The road also hints at demographic realities the town – and Japan more broadly – are currently facing: A construction crew along the route consists solely of senior citizens. In Asuke, 40 per cent of residents are over the age of 65.

But on an upper floor of the town’s modern hospital, which sits between a slow-flowing river and a Shinto shrine on a forested hill, Misao Shimamura, a 93-year-old with oval glasses, is living out the golden years of her working-class life with a degree of comfort unimaginable to many other seniors across the developed world.

Ms. Shimamura worked part-time in a hotel for years, and at the age of 65 began working full-time as a janitor – retiring only when she was 85. The hands of her now-deceased husband, who worked as a barber, eventually shook too much to cut hair, and he was forced to work his last years at a local gas station. But despite these hardships, and despite living in a rural area, Ms. Shimamura now rests comfortably within Japan’s long-term-care insurance program, without burdening her three children. After a formal reassessment by social workers, she was upgraded from home visits and moved to the hospital’s long-term-care ward. Here, she has food, shelter, scheduled activities and the attentive care of a Filipino health care worker.

“The people here are very kind,” Ms. Shimamura says.

Misao Shimamura and her caregiver.

(Iain Marlow/The Globe and Mail)

Asuke is a microcosm of Japan’s struggle to overcome its enormous demographic challenge. Japan is already the oldest society on earth, and the country continues to age rapidly as older Japanese continue to live longer lives and younger Japanese continue to put off having children in an era of economic uncertainty.

This has left Japanese governments with little choice but to take bold action. Unlike elsewhere, such as Canada, Japanese leaders have made radical changes to the way health care is delivered in recent decades, most notably with the introduction of long-term-care insurance in 2000. The system is far from perfect, but Japan has been unafraid to improve the system as they learned its faults, and as an economic boom gave way to zero growth.

Japan, in many ways, is now grappling with the same demographic time bomb looming before Canada and much of the industrialized West over the next 10 to 20 years. But Japan’s government, businesses and society are facing these challenges earlier than others, allowing the world to learn and benefit from their stumbles, innovations and experiments.

A Lawson convenience store in Saitama City with a special

A Lawson convenience store in Saitama City with a special

section that caters to seniors and caregivers.

(Iain Marlow/The Globe and Mail)

Business opportunities

Roughly 25 per cent of Japan’s population is currently over the age of 65, compared to just 16.1 per cent in Canada. But in Japan, this demographic is forecast to make up a full 40 per cent of the country’s population by 2060, the same percentage as in many rural areas emptied of young people today, such as Asuke, where the hospital says there are no trainee nurses.

Between 2010 and 2060, the percentage of Japanese citizens over the age of 75 will more than double from 11 per cent to 27 per cent, according to the government. The absolute number of old people will soon level off in Japan, but the proportion of the population who are young is declining rapidly: The percentage of Japanese younger than 19 years old, who constituted 40 per cent of the population in 1960, will decline to just 13 per cent in 2060. Japan’s total population peaked in 2010 at around 127 million people and has already begun to decline. In 2014, the country lost a record 268,000 people, as deaths continued to outstrip births.

For corporations such as Lawson Inc., a Tokyo-based convenience store chain with 12,000 stores in Japan, the country’s aging society is a reality, as well as a business opportunity.

At a Lawson store in Saitama City, the company created a hybrid store featuring a “seniors’ salon” with a blood pressure monitor, pamphlets on municipal health care services and nursing homes, and on-staff social workers. The store also has a special section featuring adult diapers, special wipes for bathing the elderly, straw cups, a gargling basin and detergent that is tough on urine and perfect for bed mats and wheelchair coverings. Staff will also deliver heavier items, such as bags of rice or water, to local residents.

“This is Japan’s national issue,” says Ming Li, a Lawson spokesperson, as he shows off TV dinners targeted at seniors.

Japan’s baby boom has also detonated within Lawson’s own work force: The company had to raise its maximum age limit for franchisees, and is experimenting with lower part-time hours per employee and very limited tasks – for seniors who can only muster energy for a couple of hours, or can only clean or sweep, but still want to work.

Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s administration is concerned about how Japan’s aging and shrinking work force will slow down the national economy. One piece of Mr. Abe’s so-called Abenomics revival program – which also includes getting more women in the workplace – is an emphasis on new medical technologies, including experimental regenerative medicine and cell therapy. The hope is that with two new acts governing regenerative medicine to help commercialize technologies more quickly, the Japanese government can save money on future health care costs while spurring the creation of a valuable new industry – particularly in bio-medical hubs such as the one in Kobe, which features a gleaming new mini-city of medical buildings, research centres and hospitals on a man-made island near the port city’s airport.

The demographic impetus to spur new medical technologies has an intriguing Canadian connection: Vancouver-based RepliCel Life Sciences Inc. received $35-million from the Japanese cosmetic giant Shiseido Co. Ltd., which is taking the Canadian firm’s cell-based therapy for baldness into a clinical trial. Shiseido faces a mature cosmetics industry, and is hoping to cash in on the grey wave in Japan. “It’s a big, big market,” says Jiro Kishimoto, who heads Shiseido’s regenerative medicine research at the company’s lab in Kobe.

Lee Buckler, RepliCel’s vice-president of business development, notes that boomers in Japan and elsewhere are retiring in a concentrated wave that is creating a critical mass of consumers for new products.

“There’s a lot of disposable income in that population,” he says. “And they’re willing to spend money not just to look good, but to perform at a higher level than geriatric people would have in the past.”

Long-term-care insurance

On a macro level, Japan’s predicament is prosperity, which is always followed by lower fertility rates and higher life expectancy. At 83.4 years, Japan has the longest life expectancy at birth in the world, according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Many Japanese people are also fearful of the type of immigration that has sustained slow population growth in the industrialized West.

In recent years, the challenge has been heightened by changes in Japanese society: The elderly in Japan, similar to seniors across Asia, are less likely to live with their children, though in Japan this is still quite common (roughly 41 per cent of Japanese seniors live with a child, compared to about 80 per cent in 1960). And women, after decades of opting out of a career after giving birth, are also being encouraged by the government to re-enter the work force, something that may eventually help boost Japan’s declining labour numbers, as the government hopes, but also prevents women from acting as caregivers.

Another reason Japan aged so rapidly is because the country’s postwar baby boom between 1947 and 1949 was extremely short – cut off in part by a 1948 law that gave easy access to induced abortions – and was followed almost immediately by a prolonged period of low fertility. The young population that came from this boom were instrumental in Japan’s remarkable economic recovery, and as the country’s economic reconstruction gained speed, another small baby boom “echo” took place between 1971 and 1974, at the height of Japan Inc.’s prosperity. That surging economy allowed the Liberal Democratic Party to expand the country’s health care system as Japan aged, but by the 1990s, the enormous price tag raised the spectre of tax hikes.

“The government realized it had to change the system,” says Yoshihiro Kaneko of the National Institute of Population and Social Security Research, noting

that the system will come under renewed strain as the second baby boom generation begins to retire.

Shoppers browse at a store in the Sugamo district of Tokyo. (Kiyoshi Ota/Bloomberg)

Shoppers browse at a store in the Sugamo district of Tokyo. (Kiyoshi Ota/Bloomberg)

Japan chose to supplement its national pension plan with long-term-care insurance (LTCI), which was implemented in 2000. Professor Nanako Tamiya, a Japanese health care expert writing in The Lancet, called LTCI “one of the most generous long-term-care systems in the world in terms of coverage and benefits.”

It is incredibly comprehensive, and removes the anxiety and unpredictable nature of elderly care elsewhere. People pay into the system starting in their 40s and are eligible to receive benefits starting at 65, or earlier in the case of illness. When they apply, applicants are interviewed by a municipal employee who feeds the resulting information into an algorithm that assigns the person a care level. That, in turn, is analyzed by an expert committee of welfare workers. A care plan is then drawn up, allowing the patient to choose between competing institutions and service providers offering everything from home visits, bathing and help getting groceries to paying for short stays in hospitals or long-term residence in nursing homes and specialized group homes for dementia patients.

The LTCI system covers up to $2,900 a month in services, as opposed to cash payment, and does require “co-payments” from patients. LTCI co-payments are capped or waived for low-income individuals, and the system saves money by providing options other than full-on institutionalization.

by Topic

DISCLAIMER:

The information in these press releases is historical in nature, has not been updated, and is current only to the date indicated in the particular press release. This information may no longer be accurate and therefore you should not rely on the information contained in these press releases. To the extent permitted by law, RepliCel Life Sciences Inc. and its employees, agents and consultants exclude all liability for any loss or damage arising from the use of, or reliance on, any such information, whether or not caused by any negligent act or omission.

THIRD PARTY CONTENT

Please note that any opinion, estimates or forecasts made by the authors of these statements are theirs alone and do not represent opinions, forecasts or predictions of RepliCel Life Sciences Inc. or its management. RepliCel Life Sciences Inc. does not, by its reference or distribution of these links imply its endorsement of, or concurrence with, such information, conclusions or recommendations.